"...volcanic activity must be considered a serious environmental hazard and risk for the Australian mainland. " Source: The risk of volcanic eruption in mainland Australia - E. B. Joyce

Select an article on this page.

Select an article on this page.

Volcanoes.

1: The Western Victorian Volcanic Plains.

2: Is there a risk of a volcanic eruption ?

3: Australian Volcanism over the last 60 million years.

4: Australia's hotspot and the creation of a new volcano.

5: Seafloor Imaging - Topography of South East Australia.

6: Active Australian Volcanoes.

Earthquakes.

7: Earthquake and Fault Line Maps for Australia..

8: Fault Line Map for Port Phillip and Burnley Tunnel.

9: Fault line and Earthquake map of Adelaide South Australia.

10: The big earthquake still building in South East Australia.

11: Tectonic plates and Fault Line Map for Asia - Pacific region.

12: Earthquake could hit Australia's capital cities.

Other related articles.

Human Induced Earthquakes - Seismic activity.

Why does the Mt.Gambier Blue Lake change colour ?

View all Alerts and News Feeds

Daily Australian Earthquake activity Reports

Daily Earthquake activity Reports latest news feed

View Local and World Earthquake Monitor and Maps

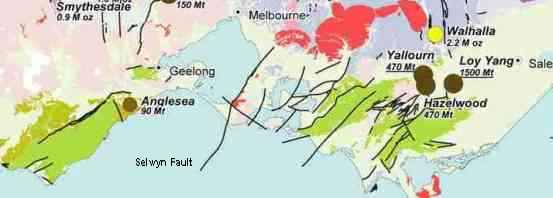

Fault Line and Gold fields

Map of Victoria.

Recent Volcano Observatory Activity Reports

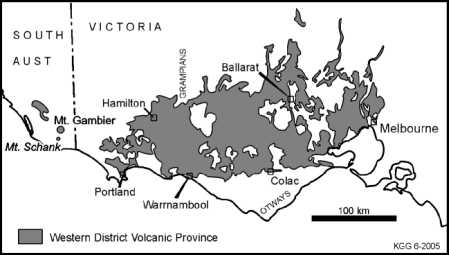

The Western Victorian Volcanic Plains are the third largest in the world and exceeded only by the Deccan in western India, and the Snake River Plateau in the United States ( Idaho-Nebraska ).

The Victorian Volcanic Plains are located

in Western

Victoria and covers over 2.3

million ha (10.36% of the State).

It

stretches from Portland in the west

to Craigieburn in the east and from

Clunes in the north to Colac in the

south.

Climate and geology.

The Victorian Volcanic Plain bioregion is characterised by vast open areas of fertile

plain covered with grasslands and grassy woodlands, and small patches of open

woodland.

The bioregion is interspersed with stony rises and numerous extinct

volcanic eruption points, denoting old lava flows and numerous scattered large

shallow lakes and wetlands.

Few major rivers cross the plain, the most significant of

these include the Barwon, Hopkins, Leigh, Maribyrnong, Wannon and Werribee

Rivers and Mount Emu Creek and their tributaries.

The basalt plain was formed by extensive volcanic activity mostly from the Upper

Cainozoic era (Quaternary) from approximately 6 million years ago to as recently as

7,200 years ago at Mt. Napier.

Several types of lava flows occurred including sheet

flows and constricted flows along valleys.

Irregular and chaotic stony rises occupy

large areas of the plains.

Numerous volcanic cones dot the landscape with scoria

cones being the most common (e.g. Mt Elephant, Mt Napier and Mt Noorat)

although some basalt cones are present (e.g. Mt Cottrell).

Soils are generally

shallow reddish-brown to black loams and clays (Conn 1993). They are fertile and

high in available phosphorous.

Older flows in the Cressy and Hamilton areas have

allowed a greater development of deep soils.

Dark saline soils occur around the

margins of some lakes.

Amongst the basalt are geological remnants that precede

and survive the period of vulcanism that produced the “Plain”.

The majority of the

elevation is below 250 m above sea level, however the maximum height does reach

720 m above sea level at two locations, Mount Doran and Mount Egerton, east of

Ballarat.

Most of the region receives between 500 and 700 mm of rain per annum (Conn

1993) with rainfall distributed relatively evenly throughout the year except in the

higher rainfall areas of the south west which receive a higher proportion of rainfall in

winter.

The general pattern of climate is one of gradation rather than fluctuation.

Average yearly rainfall generally decreases from southwest to northeast across the

region.

Annual average rainfall figures are 840 mm for Portland, 720 for Colac, 680

for Hamilton, 630 at Skipton, 530 at Cressy and 450 at Eynesbury.

The warmest

months are January and February with mean maximum temperatures ranging from

about 20° to 27°C.

In winter the mean maximum is as low as 10°C with a mean

minimum of 3°C.

| Major Vegetation Group | Area (ha) | % total extent |

|---|---|---|

| Cleared / modified native vegetation | 1,998,844 | 92.4 |

| Eucalyptus tall open forests | 656 | 0 |

| Eucalyptus open forest | 34,392 | 1.6 |

| Eucalyptus low open forest | 40 | 0 |

| Eucalyptus woodlands | 49,616 | 2.3 |

| Acacia forest and woodlands | 180 | 0 |

| Melaleuca forest and woodlands | 4 | 0 |

| Other forests and woodlands | 708 | 0 |

| Eucalyptus open woodlands | 1,020 | 0 |

| Mallee woodlands and shrublands | 1,932 | .1 |

| Low closed forest and closed shrublands | 4,484 | .2 |

| Other Shrublands | 852 | 0 |

| Heath | 36 | 0 |

| Tussock grasslands | 4,512 | .2 |

| Other grasslands, herblands, sedgelands and rushlands | 872 | 0 |

| Chenopod shrub, samphire shrub and forblands | 9,320 | .4 |

| Mangroves, tidal mudflat, samphire and bare areas, claypan, sand, rock, salt lakes, lagoons, lakes | 54,724 | 2.5 |

Is there a risk of a volcanic eruption ?

Volcanoes in eastern Australia that have not

erupted in thousands of years still pose a threat and emergency

services should be better prepared, an expert told a geology

conference today.

But another expert thinks Australia should

be more worried about fires, storms and earthquakes than

volcanoes.

Bernie Joyce, from the

University of

Melbourne, presented a paper on volcanic hazards today at the

17th Australian

Geological Convention of the

Geological Society of Australia held in Hobart,

Tasmania (1a).

Volcanoes in Victoria, New South Wales and

Queensland could erupt at any time, he told ABC Science

Online ahead of the conference.

There has been no

volcanic activity in Australia in the past few hundred years, and no

major eruption since Mt Gambier, on the border of South Australia

and Victoria, 4500 years ago.

But a sudden eruption could

still catch emergency authorities unprepared for the floods, mud

flows and ash falls that could follow, said Joyce.

He said

the kind of eruption Australia could expect was not on the same

scale of the Mt Helen's eruption, which wiped out a large area in

the U.S. state of Washington in May 1980. Australia could expect a

smaller eruption.

According to Joyce, an eruption could

either be an explosion like the one at Mt Gambier, creating a big

hole in the ground, or a volcanic eruption common in Queensland and

Victoria in the past 50,000 years of a different type.

These

eruptions have large lava flows followed by a more gaseous eruption

where the lava breaks up into small pieces and builds a cone of

cinders and sharp rock material.

There is evidence of these

cones and crater lakes around Victoria and northern Queensland,

Joyce said.

"In either case you wouldn't get much warning and

you would be working out what to do when it came," Joyce

said.

Eastern Australia had up to 20 volcanoes less than

50,000 years old, said Joyce, who said probability showed these

still posed a threat. He warned the consequences of even a

small eruption coming into contact with groundwater could include

hot, wet ash falls, dangerous gases and ash blown into the air,

damage to animals and the environment, and pollution in water

systems.

Map courtesy (2)

Map courtesy (2)

“ There are around 400 volcanoes stretching from the Western District of Victoria

into the Western Uplands around Ballarat and to the north of Melbourne around Kyneton

and Kilmore, in some parts of the Eastern Uplands such as to the north of Benambra,

and across to the South Australian border near Mt Gambier.

A volcanic eruption in

the Western Uplands could potentially see lava flows and ash falls impacting on Melbourne.

There is also similar volcano risk present in various provinces in Far North Queensland,

stretching from south-west of Townsville to near Cairns and up to Cooktown in the

Far North. There are more than 380 volcanoes in total across this part of Queensland.

A future eruption in any of these regions would be unlikely to come from an existing

volcano (as the volcanoes there are generally considered to be 'once only’ erupters).

Rather, future eruptions would occur at new sites nearby.

The geological record shows

that new volcanoes in these areas have erupted perhaps every 2000 years in the past

40,000 years—and given there has not been a major eruption there for the past 5000 years,

a significant eruption seems well overdue. " (3)

Reference http://www.17thagc.gsa.org.au/

Many of Victoria's youngest volcanoes are scoria cones. Among them are Mount Elephant near Derrinallum, Mount Noorat near Terang, and Mount Fraser near Beveridge, north of Melbourne.

There are 200 steep-sided scoria volcanoes scattered across Victoria's basalt plain. They were formed when magma interacted explosively with groundwater, blasting molten rock high into the air in spectacular and violent displays.They were true 'fire mountains' when they erupted.

The usual warning signs.

But Dr Wally Johnson,

head of the geohazards division at Geoscience Australia told ABC Science

Online that Australia's government geological science

organisation was more concerned about hazards posed by fires, storms

and earthquakes than volcanoes.

"Australians are more likely

to face risks from volcanoes when flying to Southeast Asia or the

South Pacific and ash from volcanoes getting into the jets and

causing problems with aircraft," said Johnson.

While Johnson

said that Joyce did a good job raising awareness of the risks posed

by volcanoes, he said there were other hazards with higher

priorities.

"If Mt Gambier did erupt it would impact on local

communities," Johnson said. "But any changes to the state of these

volcanoes would be noticed early on, either through earthquakes, or

in the case of Mt Gambier an increase in the temperature of the

water.

"We know that volcanoes do provide a fair bit of

warning. In most cases this would be months or even years. You might

get a volcano way out in western Victoria where you might not notice

the warning signs but in most cases you'll get advance warning from

geological phenomena," he said.

Advance warnings could

include an increase in seismic activity, a change in the temperature

of surface soils, or even smoking fumaroles, small eruptions from

the side of a volcano that indicate that a major eruption was

imminent.

Aborigines witness volcanic eruptions:

Dingo bones and an Aboriginal grinding stone were recovered from beneath tuffs

at Tower Hill near Warrnambool in Victoria.

In 1953 Gill observed that “ At Mt Gambier in South Australia,

implements and hearths have been found beneath the volcanics, and

archaeological dating and radiocarbon dating are possible. "

The

eruption at Mount Gambier has now been dated to between 4.3 and

4.6 KYA using plant material embedded in the volcanic deposits

(Sutherland, 1995:32). In a number of places in Victoria, too,

artefacts have been found beneath volcanic material (Gill 1953).(4)

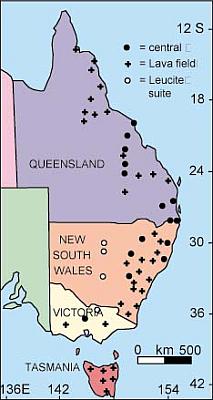

Vulcanologists have

divided this volcanic activity into lava fields - areas where large

amounts of lava flowed from diffuse dykes and pipes over a wide area

(shown in red); and central volcanoes - areas where volcanism was

produced from either a single central vent or a cluster of vents

(shown in orange).

It is now thought that the central volcanoes were

produced as the Australian continent moved over a hot spot in the

underlying mantle which 'melted' through the plate to form the

volcano. As the continent moved northward, the stationary hot spot

formed volcanoes further to the south on the continent. Therefore

the rocks of central volcanoes down the east coast become younger as

you move southward.

Map courtesy. http://www.ga.gov.au/archive/volcanoes/

|

|

Distribution

of volcanoes in eastern Australia.

Volcanic centres

1 Byrock, 2 El

Capitan, 3 Cargelligo, 4 Cosgrove;

Central volcanoes

5 Nadewar, 6 Warrumbungle,

7 Canobolas, 8 Macedon, 9 Ebor,

10 Comboyne;

Lava fields

11 central, 12

Doughboy, 13 Walcha, 14 Barrington, 15 Liverpool Range, 16 Dubbo, 17 Kandos, 18

Sydney 19 Abercrombie 20 Grabben Gullen, 21 Southern Highlands 22 Monaro 23

Snowy Mountains, 24 South Coast, 25

Older Volcanics, 26 Newer Volcanics.

Volcanic centres in Queensland. Compiled from Sutherland (1995) and Johnson and others (1989).

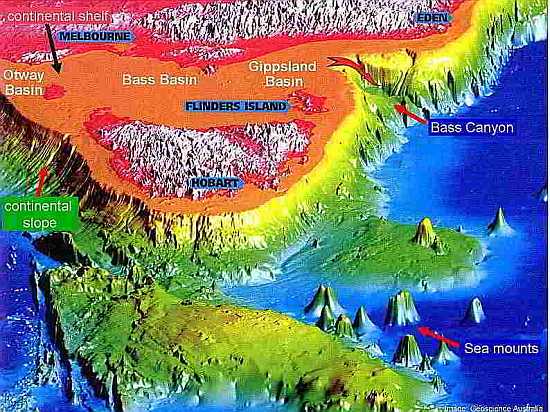

Hotspot system in our backyard

We have a hotspot system of our very own. Australia's hotspot currently lies under Victoria, Bass Strait, Tasmania, and the floor of the Tasman Sea at a latitude of about 40°S. It's one of more than a hundred systems identified around the world.

As far as hotspots go, the one in our backyard is slumbering. Present hotspot activity is possibly confined to the triggering of earthquakes in predicted areas, such as the recent event off the coast of north-west Tasmania, and deep gas discharges under Victoria and Tasmania.

Scientists believe a new Australian volcano is being created.

Geologists suspect an earthquake that originated 50 kilometres from King Island in February 2002 signalled the reawakening of the hot spot, a region in the Earth's crust where the planet expels some of its internal heat.

Geologists suspect an earthquake that originated 50 kilometres from King Island in February 2002 signalled the reawakening of the hot spot, a region in the Earth's crust where the planet expels some of its internal heat.

Australia's hot spot is several hundred kilometres wide and lies under Bass Strait and parts of Victoria and Tasmania.

Wally Johnson, a vulcanologist at Geosciences Australia, said the fact that there were earthquakes taking place in the area "means that geologically, the hot spot has to be regarded as active, even though it hasn't produced volcanic eruptions as such".

He said it could spawn a volcano within 100 years.

One chain of about 13 volcanoes begins in north Queensland.

The largest in this chain is the Tweed Volcano, where Mount Warning represents the main vent. The chain extends south from the Cape Hillsborough Volcano in north Queensland through to the Mount Macedon Volcano in Victoria.

Other volcanoes in the chain include the Glasshouse Mountains, the Warrumbungles and Canobolas near Orange. The volcanoes are quite young. The oldest ones are found in north Queensland, while the youngest are in Victoria - the most northern volcano formed around 33 million years ago.

Distribution of Cenozoic volcanism on the Australian plate.

a, White arrows show location of s-shaped bends in the Tasmantid and Lord

Howe seamount tracks. Hotspot-derived central volcanoes are shaded black;

non-hotspot mafic lava fields are grey, and seamount tracks are outlined in

white. White circles show predicted present-day hotspot locations. The

oldest total-fusion 40Ar–39Ar ages for Tasmantid seamounts are shown in

black to the left of the chain; calculated ages are shown in white to the right of

the two tracks at 5-Myr intervals.

b, Locations of silicic rocks (shown in red) from the central volcanoes

(outlined in blue and dashed where approximate) sampled for 40Ar–39Ar

geochronology.

".....our evidence for a brief period of altered plate motion

between 26–23 Myr rests on the assumption that central volcanoes in

eastern Australia are generated over a relatively stationary hotspot."

Source and image courtesy of: Rapid change in drift of the Australian plate records

collision with Ontong Java plateau. Kurt M. Knesel, Benjamin E. Cohen, Paulo M. Vasconcelos & David S. Thiede Earth Sciences, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, 4072, Australia - Nature Vol 454 7 August 2008

SEAMOUNTS

A seamount is an underwater mountain, often of volcanic origin, defined as a steep geologic

feature rising from the seafloor reaching a minimum height of 1,000 meters and with a limited

extent across its summit.

The definition, however, is not strictly adhered to and any steep undersea mountain is often

referred to as a seamount, regardless of its size.

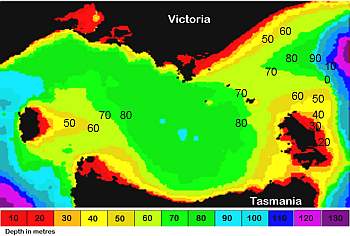

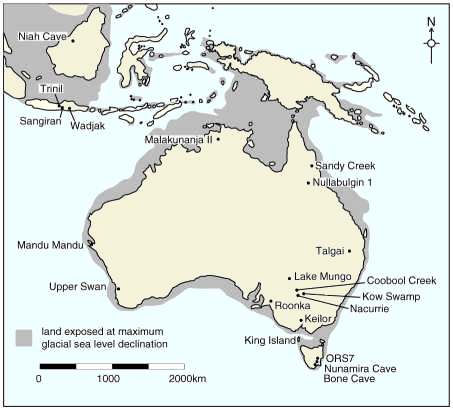

During glacial sea level declination Tasmania was connected to the Australian mainland, with the existing islands forming hills in the

Bassian Plain.

People could have easily walked to Tasmania from what is now the State of Victoria.

South-western Tasmania was occupied by 30,000 BP, suggesting that Tasmania was initially colonised during the low sea level phase of 29,000 to 37,000 years BP (Cosgrove, et al., 1990).

Sea levels rose and flooded the Bassian Rise connecting Victoria to Flinders Island and north-eastern Tasmania between 12,000 and 13,500 years BP (Jennings, 1971; Chappell and Thom, 1977).

The Tasmanians apparently did not have adequate watercraft to cross Bass Strait, or reach the major islands within it, so with high sea levels came isolation.

The precise date of the first human occupation of Australia is not known, estimates range from 30,000 to 60,000 years ago.

The Aboriginal people are thought to have crossed to Australia from south-east Asia.

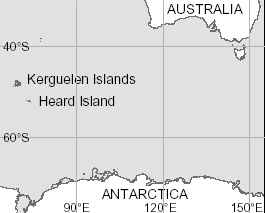

Active Australian Volcanoes.

Heard Island and McDonald Islands is a subantarctic island group located in the Southern Ocean, about 4100 kms southwest of Western Australia.

The islands and surrounding waters teem with wildlife and other natural wonders that make it a special place.

Heard Island consists of 2 volcanic cones, Big Ben and Mt. Dixon, joined by a narrow isthmus. Both cones are young, but only Big Ben has been observed to erupt.

Big Ben is a large, glacier-covered, composite cone 20-25 km in diameter at sea-level, consisting mainly of basaltic lavas and lesser ash and scoria. Its summit region consists of a SW-facing semi-circular ridge 5-6 km in diameter, 2200-2400 m above sea-level.

2008, 2007, 2006, 2003-04, 2000-01, 1993, 1992, 1985-87, 1954, 1953, 1950-52, 1910, 1881?

McDonald Island began erupting in 1992, after lying dormant for 75,000 years. It has erupted several times since with satellite pictures in 2001 showing that the island had doubled in size. The initial evidence came in the form of abundant pumice washing up on beaches north and south of The Spit at the eastern extremity of Heard Island, directly to the east of McDonald island.

This is Australia's second currently active volcano.

The first reported earthquake in Australia was felt at Port Jackson (Sydney) in June 1788, when Governor Phillip reported:

"The 22nd of this month we had a slight shock of an earthquake; it did not last more than 2 or 3 seconds. I felt the ground shake under me and heard a noise that came from the southward, which I at first took for the report of guns fired at a great distance."

Similar earthquakes were felt in the early days of Adelaide (1837), Melbourne (1841), Hobart (1827) and Perth (1849).

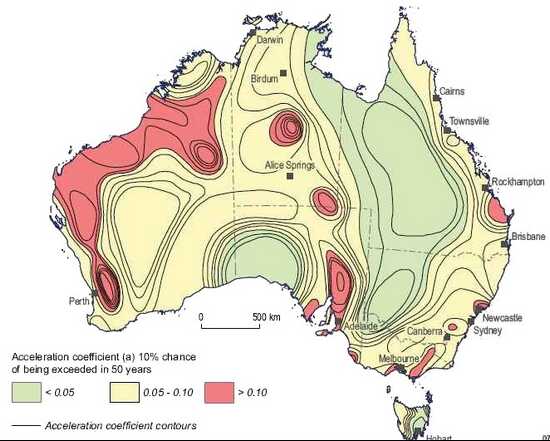

The map shows earthquakes with

Richter magnitudes greater than 3.5 and suggests the higher seismicity and hazard regions

are along eastern Australia (in bands running from Melbourne to Newcastle, Brisbane to Gladstone,

and Mackay to Cairns), in the Adelaide geosyncline, and in parts of Western Australia.

Less seismographs and lower population density during the last century in Queensland

relative to eastern NSW and Victoria means that the true seismicity in Queensland compared

to eastern NSW and Victoria may be higher than it appears on the map.

Among Australian cities, Adelaide share with Perth the dubious distinction of being the most

dangerous place seismically, although on a world scale the risk is slight and the estimated recurrence

period of a 1954-sized earthquake is about 100 years.

The largest known South Australian earthquake occurred at an epicentre near Beachport in the South-East

on 10 May 1897. It has been assigned an intensity of 9 and a magnitude of 6.5.

On 19 September 1902 an

earthquake of somewhat smaller magnitude occurred at Warooka on southern Yorke Peninsula. Both the Beachport and Warooka shocks were clearly felt in Adelaide.

South Australian earthquake epicentres occur

in two main seismic zones. The major zone, within the Adelaide Geosyncline, extends from Kangaroo Island

through the Mount Lofty Ranges and Flinders Ranges to Leigh Creek.

The second seismic zone is on

Eyre Peninsula where some epicentres may be associated with the Lincoln Fault. There are two other zones,

one near Kingston SE, and the other in the Simpson Desert in the far north - possibly the most active

seismic zone on the Australian continent.

Source: "Atlas of South Australia | Natural Hazards" http://www.atlas.sa.gov.au/

| Greater than 0.10 | Between 0.05 and 0.10 | Less than 0.05 |

The numbers, e.g., "greater than 0.10”, refer to the ground acceleration (measured as a fraction of the Earth’s gravitational acceleration, g, i.e., 1.0 g = 9.8 m/s2) with a 10% probability of being exceeded in 50 years.

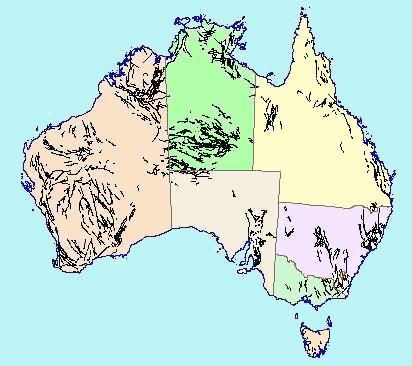

Earthquakes occur in Australia even though the nation does not sit on a tectonic plate boundary.

The nearest boundary passed through Papua New Guinea to the north, into the Pacific Ocean and south to New Zealand.

Australia experiences "intraplate earthquakes" along fault lines dating back millions of years when parts of the country were on or near plate boundaries.

The greatest earthquake risk in Queensland is in Central Queensland.

A fault line just 30 kilometres west of Bundaberg ( the origin of a quake at least 5.4 in magnitude in 1935 )

has the potential for another large earthquake.

Source: Central Queensland Seismology Research Group April 24, 2009

"There are probably lots of active faults that could generate earthquakes in places that haven't had earthquakes yet." Source: Professor Paul Somerville, Macquarie University.

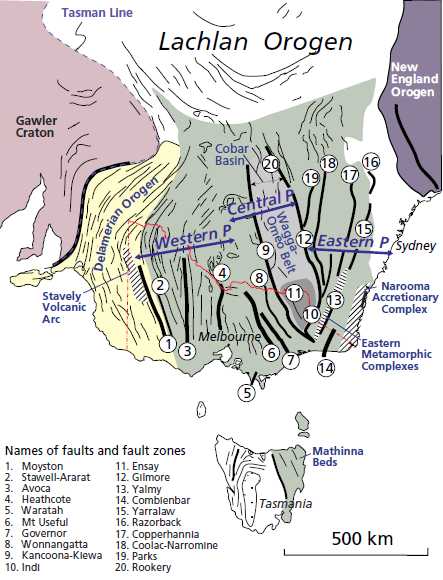

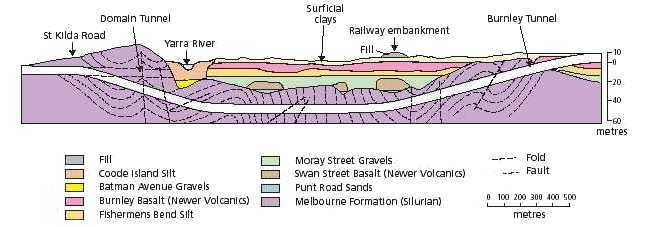

Major Geological Fault Lines located in south eastern Australia.

Some of the fault lines around Melbourne are:

Selwyn's Fault and the parallel Tyabb Fault - Mornington Peninsula.

Beaumaris Monocline transected by the perpendicular Melbourne Warp

under the south-eastern suburbs.

Multiple fault lines running from Gippsland to the eastern aspect of

Westernport Bay.

Rowsley Fault - north-west of Geelong running northwards to Bacchus

Marsh.

Barrabool Fault - running west from Geelong to Colac

Bellarine Peninsula fault, parallel to Selwyn's Fault.

Torquay Fault - running along coastline.

The Earth’s surface

consists of interlocking plates.

Most plates comprise both

continents and ocean floors. The

original concept of continental

drift emphasised continents

because that was where the rocks

were mapped and the connections

drawn. However, we now use the

term ‘plate tectonics’ because it is

the plates that are moving, and

the continents are being carried

upon them. The main plates

are named in the figure.

Two major,

modern mountain belts have

formed at convergent margins:

the Himalaya and the Andes.

The Indo-Australian plate

carries two continental masses

(Australia and India) and three

smaller masses (Papua New

Guinea and the north island and

the western side of the south

island of New Zealand).

To the

south of Australia the ocean

floor is spreading as the Indo-

Australian plate moves away

from Antarctica. To the north,

the plate is converging with Asia.

The plate motion shown is as

measured at Darwin: 67 mm/yr

in the direction 35° east of north.

Tonga in regard to the large tectonic blocks of the new global tectonics.

Heavy lines are island arcs or arc-like features.

Tensional (divergent arrows) and compressional

(convergent arrows) indicate relative movements at margins of blocks;

length of arrows is roughly

proportional to rate of relative movements. Some historically active volcanoes are indicated by X.

Open circles represent earthquakes that generated tsunamis (seismic sea waves) detected at

distances of 1,000 or more kilometres from their source. The six major tectonic blocks are shown

Modified from Isacks, Oliver, and

Sykes (1968).

Experts warn a major earthquake could hit Australia's capital cities.

According to Seismologist Dr Kevin McCue of Central Queensland University in Rockhampton, the

Australian continent is hit by a magnitude 6 earthquake every five to six years

and currently, one is overdue, " so we're just waiting to see what will happen in Victoria ", and he thinks

that it is just luck we haven't had an earthquakes under Melbourne and Sydney.

Earthquakes frequently occur close to plate boundaries, where the plates that make up the earth's crust

push and slide against each other.

Despite sitting in the middle of a tectonic plate, scientists say Australia is subjected to the stresses

and strains from movements at the edges of plate boundaries. "Compared to Canada, US, South Africa, central Africa and India, Australia is more active,"

US seismologist Professor Paul Somerville, deputy director of Risk Frontiers, based at Macquarie University

in Sydney, says Australia is under "quite high tectonic stress". "As is the case in other stable regions,

the earthquake activity appears to be generally higher around the margins (edges) of the continent than in its

interior," he says. "Since Australia's population is more concentrated on its coasts than other stable regions,

this by itself presents a higher hazard level."

Australians are "complacent" to the risks posed by earthquakes and that one could strike a major city, say earthquake experts.

The warning comes after two moderate-sized earthquakes recently struck the Gippsland town of Korumburra in southeast Victoria. 06/03/2009

Both were felt 120 kilometres away in the city of Melbourne.

The earthquakes registered magnitude 4.6 on the Richter scale, with another small earthquake felt in the area in January 2009.

Both struck 15 kilometres below ground and were associated with uplift of the Strzelecki Ranges.

Source: Australians 'complacent' to earthquakes ABC Science Friday, 27 March 2009

Two separate geological studies have concluded that an area from

Adelaide to south-east Victoria is seismically active and the next

'big

one' could endanger lives and infrastructure.

Contrary to the popular notion that Australia is an ancient continent

that has for millions of years been geologically comatose, University of

Melbourne geologists have uncovered evidence that parts of South-eastern

Australia recently stirred from their geological slumber and are in an

active mountain building phase. These mountains are being shaped by

earthquakes, some reaching greater than 6 on the Richter

scale.

"When these big quakes reoccur, they have the potential to

cause catastrophic damage to cities such as Melbourne, Adelaide, and the

La Trobe Valley area, which straddle some of these major faults lines,"

says Professor Mike Sandiford, who conducted one of the studies.

Possibly, the most dramatic indication of this geological

stirring, which the studies estimate began suddenly about ten million

years ago, can be found in the landscape of the Mount Lofty Ranges near

Adelaide.

"Some faults around Adelaide have moved slabs of the

continent up to 30 metres in the last one million years," says Sandiford.

"A typical earthquake of magnitude 6.0 might produce a

displacement of about one metre. Thirty metres is equivalent to 30-50 big

earthquakes in the last million years," he says.

Other areas of

intense mountain building have been around Victoria's Otway Ranges,

Mornington Peninsula and Strzeleckis. In some of these areas, similar

uplift and erosion over the last 10 million years have thrust chunks of

Australia upwards in the order of one kilometre.

Tectonic

movements have pushed the Otways 250 metres higher in the last three

million years, and The Selwyn fault, which runs from Mt Martha, on

Victoria's Mornington Peninsula, east to the Dandenong Ranges has possibly

produced six metres of uplift in the last 100,000 years.

"This is

potentially six big earthquakes," says Sandiford.

"We are still

trying to determine the slip rates along these fault lines, but our

evidence so far suggests that we should expect, on any one of the major

faults, a large earthquake every 10-20,000 years. The estimated return

period of a quake greater than 6.0 in south-east Australia is about 30

years, but none have been recorded in the last 100 years," he says.

"Most earthquakes experienced by this region are less than three

on the Richter scale and occur several times a year. It is unusually quiet

at the moment with nothing over 1.5 for the last few months."

Sandiford's evidence for the mountain building comes from

extensive airborne geophysical data that measure radioactivity and

magnetic field of the soil and rock. Rocks of different ages and types

display different levels of radioactivity and magnetic properties. Faults

and uplift which bring older rocks to the surface or bury younger strata

can be detected through such measurement.

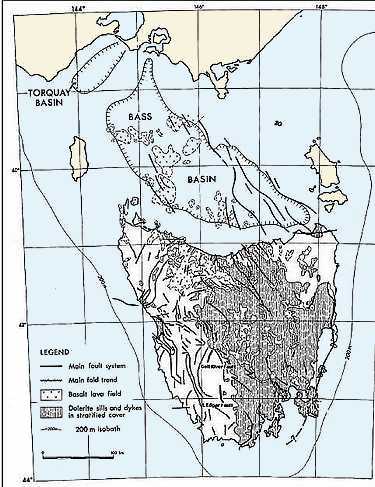

A second study led by

the University's Dr Malcolm Wallace investigated sediments and seismic

data from petroleum surveys to determine the long-term history of

earthquakes and seismic activity in South East Australia.

Evidence

of faulting, buckling and uplift can be clearly seen in the young sediment

record from this region. The team obtained an age for the various faults

and folds by using a combination of fossils and radioactive isotope dating

methods.

The findings confirm that the young mountain building and

earthquake activity began around 10 million years ago and continues to the

present day.

"This young faulting and folding has had very

important economic effects for Australia. The giant oil and gas fields of

the Gippsland Basin are largely trapped in young geological deformations

produced by the seismic activity. Faulting, however, can also rupture the

reservoirs and cause leakage.

"In the La Trobe Valley it is this

tectonic activity that has made the thick sequences of brown coal that

Victoria relies on for its power generation economically accessible," says

Wallace.

In the Murray Basin, the same activity was largely

responsible for the heavy mineral deposits such as titanium and rare

earths. It also caused the damming of the Murray River only 60,000 years

ago forming the Barmah Swamp near Echuca, Victoria.

"While this is

still nothing compared to the activity along the plate margins of, for

example, New Zealand and California, it defies the notion that Australia

is an inactive continent."

Dr Wallace's research team is

Julie Dickinson (PhD student) and Dr Guy Holdgate, all from the

University's Department of Earth Sciences.

Other Articles

Drought and Bush Fires in Victoria 1851 Black Thursday

Chronology of Australian Major Bush fires

Chronology of Australian Major Droughts

Archaeological site at Mount William Stone Hatchets.

Megafauna bones found at Lancefield - Giant Kangaroo.

Source for cited articles and reference material:

Reference: Bernie Joyce School of Earth Sciences

The University of Melbourne http://web.earthsci.unimelb.edu.au/Joyce/joyce.html

• Reference: ABC Science Online http://www.abc.net.au/science/news/

• Reference: Geoscience Australia http://www.ga.gov.au/

• Reference: Australian Antarctic Division http://www-new.aad.gov.au/default.asp?casid=2099

• Reference: Australian Antarctic Division http://www-new.aad.gov.au/default.asp

• Reference: Global Volcanism Network's

http://users.bendnet.com/bjensen/volcano/indian/indian-heard.html

• Reference: Volcanoes & Earthquakes in SE Australia http://www.seismicity.segs.uwa.edu.au/welcome

• Photograph of South Australian Volcano

Courtesy. Office of Minerals & Energy Resources, South Australia.

• Images from poster by B. Joyce (University of Melbourne), Cities on Volcanoes Conference, Auckland, N.Z. Feb 2001

• Map courtesy. http://www.ga.gov.au/archive/volcanoes/

• Map Tasmania fault lines courtesy. The Lake Edgar Fault: ANNALS OF GEOPHYSICS, VOL. 46, N. 5, Oct 2003

• Reference: Sutherland, L., 1995, The Volcanic Earth: Sydney, University of New South Wales Press, 248 p.

• Reference: Johnson, R. W. (ed) 1989a. Intraplate alkaline volcanism in eastern Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 408pp.

(1) Source: Australian Natural Resources Atlas http://www.environment.gov.au/index.htm

(1a) Source: 17th Australian Geological Convention 4 February 2004

(2) Source: Australian Natural Resources Atlas http://www.environment.gov.au/index.htm

(3) Source: Science Alert http://www.sciencealert.com.au/news/20092109-19788.html

Accessed 24th Sep 2009

(4) Source: Humans and Volcanoes in Australia and New Guinea. Peter Bindon and Jean-Paul Raynal

(5) Reference: Geoscience Australia http://www.ga.gov.au/

(6) Source: Gray et al Chapter 2 Structure, metamorphism, geochronology and tectonics of Palaeozoic rocks.

ftp://129.78.124.227/.../Gray_etal_Victoria_Paleozoic_rocks_GeolVic.pdf

Source: http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/03/40/67/PDF/Australie_volcans.pdf

Source: ABC Science Online

http://www.abc.net.au/science/news/stories/s1042020.htm

Image: Seafloor Imaging Courtesy Geoscience Australia http://www.ga.gov.au/

Source: Gill, E.D., 1955. Radiocarbon dates for Australian archaeological and

geological samples. Aust. Jour. Sci. 18:49-52.

Source: Sutherland, L., 1995. The Volcanic Earth. (University of New South

Wales Press, Sydney)

References and further reading.

United Nations - Asian and Pacific Training Centre for Information and Communication Technology for Development.

United Nations - ICT for Disaster Management: Real life examples © IDD-ESCAP, 2011

Download: United Nations - ICT for Disaster Management: Real life examples © IDD-ESCAP, 2011

•

Ashley, P. M., Duncan, R. A., Feebrey, C.

A., 1995. Ebor Volcano and Crescnet Complex, northeastern New South Wales: age

and geological development. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 42, 471-480.

• Ernst, R. E., Buchan, K. L., Campbell, I. H., 2005, Frontiers in large

igneous province research. Lithos 79,

• Ferrett, R. R. 2005. Australia’s volcanoes. New Holland Publishers (Australia), Sydney, 160pp.

• Johnson, D., 2004. The geology of Australia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 276 pp.

• Johnson, R. W. (ed) 1989a. Intraplate

alkaline volcanism in eastern Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 408pp.

• Johnson, R. W. 1989b. Volcano distribution

and classification. In: Johnson, R. W. (ed), Intraplate alkaline volcanism in

eastern Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 7-11.

• Johnson, R. W., Taylor, S. R., 1989. Introduction

to intraplate volcanism – preview. In: Johnson, R. W. (ed), Intraplate alkaline

volcanism in eastern Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge University Press, Sydney.

• Lewis, G. B., Mattox, S. R, Duggan, M.,

McCue K. 1998. Australian volcanoes educational slide set. Australian Geological

Survey Organisation, Canberra

• Sutherland, F. L.

1998. Origin of north Queensland Cenozoic volcanism: relationships to

long lava flow basaltic fields, Australia. Journal of Geophysical

Research 103, 27347-27358.

•

The Volcanism Blog: Australia ‘overdue’ for volcanic eruption?