Early Settlers' Homes and Bush Huts in Australia.

Select an article on this page.

Select an article on this page.

1: Introduction:

2: First European settlers at Sydney Cove in 1788

3: Extract from the Journals of Watkin Tench 1788.

4: A wattle and daub house

5: Shell lime was burnt from oyster shells.

6: A Description of Australian Bush Huts circa 1822

7: Naraigin sheep station Buildings circa 1850's

8: A hessian and corrugated iron Hotel 1892.

9: Early Settlers Homes in Victoria circa 1860.

10: Adobe or mud brick construction mid 1800's

11: 1901 Census of Australian Dwellings and their types.

12: Built for the bush: The green architecture.

Introduction.

The first European settlers who arrived in Sydney Cove in 1788 were not aware of Aboriginal construction methods.

Building with earth was not a new thing to the original inhabitants of Australia, for thousands of years prior to European settlement the indigenous Australian aboriginal people developed appropriate dwellings for their lifestyle and environment.

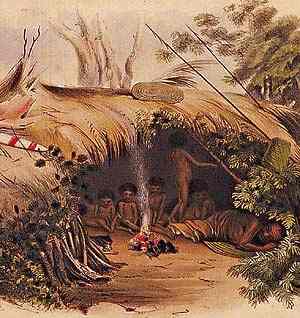

Traditional Indigenous gunyah (22)

Traditional Indigenous homes , varied from temporary windbreaks and wiltjas (shelters), small bark shelters (gunyah) (20a) built over a wooden frame of

stringybark or paperbark to substantial round houses thatched with grass for large families.

Traditional Indigenous homes , varied from temporary windbreaks and wiltjas (shelters), small bark shelters (gunyah) (20a) built over a wooden frame of

stringybark or paperbark to substantial round houses thatched with grass for large families.

The materials used for the construction of homes, varied across geographic regions of the continent and

depended on the availability and supply of materials. (20)

In the Lake Eyre region, mud was used with grass

to waterproof dome shelters and in the Western Desert, tree limbs were used for shelter frames and

spinifex for the cladding.

In the colder regions of south eastern Australia, stone huts (21) consisting of stone circles about two

metres across and 1.5 metres high were erected forming the shelter walls. Branches and vegetation were

placed over these to form a roof. In South Australia, whale bones were sometimes used as a framework

for structures.

The types of construction varied from dome frameworks made of cane through spinifex-clad arc-shaped

structures, to tripod and triangular shelters, and to elongated, egg-shaped, stone-based structures

with a timber frame, and pole and platform constructions. Annual base camp structures, whether

dome houses in the rainforests of Queensland and Tasmania or stone-based houses in south eastern

Australia, were designed for use over many years by the same family groups.

Although examples of Aboriginal dwellings are no longer in existence early European authors have described them.

The explorer Eyre wrote:" ... we found a village of thirteen huts near mount Napier, they were cupola-shaped, made of a strong wood frame covered with thick turf. " (11)

Early Australian houses were very primitive, and ranged from bough shelters with only a roof and no walls through to bush and bark huts,

log cabins, slab, wattle-and-daub, thatched and sod huts.

Since there was an abundant supply of timber, it was used for walls, roofs, floors, doors, windows and even chimneys.

Source and photo courtesy of: Forests Commission Victoria, Alps at the Crossroads, Dick Johnson

This family set up home in a giant dead tree. Note the post and rail fences each side of the tree depicting a boundary for their home.

Sydney Cove 1788

The first European settlers who arrived in Sydney Cove in 1788 soon found the small acacia trees were suitable for wattling and plastering with clay. The trees became known as wattles and the building process wattle and daub.

Governor Phillip sent out exploring parties to survey

Sydney Harbour and the river at the head of the

harbour shortly after landing at Sydney Cove. On

Sunday 2 November 1788 Governor Phillip and

others, including marines, established a military

redoubt at Rose Hill. Convicts were sent to Rose Hill

to commence farming.

With the success of farming at Rose Hill, Phillip

decided to expand the settlement.

In 1790 Governor

Phillip and Surveyor Augustus Alt laid out a town plan

with High Street (George Street) running between the

planned site of Government House and the Landing

Place to the east of this site. As set out, George

Street was 205 feet (63 m) wide and a mile (1.6 km)

long.

On either side of the street huts were to be

at a distance of 60 feet (18.5 m) from each other, with

a garden area allotted at the rear of each hut. The

huts were to be built of wattle and daub and the roof

thatched and were to be 12 by 24 feet (4 by 8 m).

The

new street and the huts were built by the convicts

from July 1790. By September 1790 bricks were

being fired for a barracks and store house, a wharf

was built just to the east of this site and 27 huts were

being built along High Street (George Street).

Extract from the Journals of Watkin Tench. Captain of the Marines at Port Jackson from 20th January, 1788, until December, 1791.

Transactions at Port Jackson in the Months of April and May. 1788

As winter was fast approaching, it became necessary to secure

ourselves in quarters, which might shield us from the cold we were

taught to expect in this hemisphere, though in so low a latitude.

The erection of barracks for the soldiers was projected, and the

private men of each company undertook to build for themselves two

wooden houses, of sixty-eight feet in length, and twenty-three in

breadth.

To forward the design, several saw-pits were immediately

set to work, and four ship carpenters attached to the battalion, for

the purpose of directing and completing this necessary undertaking.

In prosecuting it, however, so many difficulties occurred, that we

were fain to circumscribe our original intention; and, instead of

eight houses, content ourselves with four.

And even these, from the

badness of the timber, the scarcity of artificers, and other

impediments, are, at the day on which I write, so little advanced,

that it will be well, if at the close of the year 1788, we shall be

established in them.

In the meanwhile the married people, by

proceeding on a more contracted scale, were soon under comfortable

shelter.

Temporary wooden storehouses covered with thatch or shingles, in

which the cargoes of all the ships have been lodged, are completed;

and an hospital is erected.

Barracks for the military are

considerably advanced; and little huts to serve, until something

more permanent can be finished, have been raised on all sides.

Notwithstanding this the encampments of the marines and convicts are

still kept up; and to secure their owners from the coldness of the

nights, are covered in with bushes, and thatched over.

The plan of a town I have already said is marked out.

And as

freestone of an excellent quality abounds, one requisite towards the

completion of it is attained.

Only two houses of stone are yet

begun, which are intended for the Governor and Lieutenant Governor.

One of the greatest impediments we meet with is a want of limestone,

of which no signs appear.

Clay for making bricks is in plenty, and a

considerable quantity of them burned and ready for use.

3rd of November1788

A new settlement, named by the governor , Rose Hill, 16 miles inland,

was established on the 3d of November, the soil here being judged

better than that around Sydney. A small redoubt was thrown up, and a

captain’s detachment posted in it, to protect the convicts who were

employed to cultivate the ground.

The State of the Colony in November, 1790.

Cultivation, on a public scale, has for some time past been given up

here, (Sydney) the crop of last year being so miserable, as to deter

from farther experiment, in consequence of which the government-farm

is abandoned, and the people who were fixed on it have been removed.

Necessary public buildings advance fast; an excellent storehouse of

large dimensions, built of bricks and covered with tiles, is just

completed; and another planned which will shortly be begun.

Other

buildings, among which I heard the governor mention an hospital and

permanent barracks for the troops, may also be expected to arise

soon.

Works of this nature are more expeditiously performed than

heretofore, owing, I apprehend, to the superintendants lately

arrived, who are placed over the convicts and compel them to labour.

The first difficulties of a new country being subdued may also

contribute to this comparative facility.

Sydney 12th of November, 1790

Except building, sawing and brickmaking, nothing of

consequence is now carried on here.

The account which I received a

few days ago from the brickmakers of their labours, was as follows.

Wheeler (one of the master brick-makers) with two tile stools and

one brick stool, was tasked to make and burn ready for use 30000

tiles and bricks per month.

He had twenty-one hands to assist him,

who performed every thing; cut wood, dug clay, etc. This continued

(during the days of distress excepted, when they did what they

could) until June last.

From June, with one brick and two tile

stools he has been tasked to make 40000 bricks and tiles monthly (as

many of each sort as may be), having twenty-two men and two boys to

assist him, on the same terms of procuring materials as before.

They

fetch the clay of which tiles are made, two hundred yards; that for

bricks is close at hand.

He says that the bricks are such as would

be called in England, moderately good, and he judges they would have

fetched about 24 shillings per thousand at Kingston-upon-Thames

(where he resided) in the year 1784. Their greatest fault is being

too brittle.

The tiles he thinks not so good as those made about

London. The stuff has a rotten quality, and besides wants the

advantage of being ground, in lieu of which they tread it.

Such is my Sydney detail dated the 12th of November, 1790. Four days

after I went to Rose Hill, and wrote there the subjoined remarks.

Parramatta ( Rose Hill ) 16th of November, 1790

The main street of the new town is already begun.

It is to be a mile

long, and of such breadth as will make Pall Mall and Portland Place

“hide their diminished heads.”

It contains at present thirty-two

houses completed, of twenty-four feet by twelve each, on a ground

floor only, built of wattles plastered with clay, and thatched.

Each

house is divided into two rooms, in one of which is a fire place and

a brick chimney.

These houses are designed for men only; and ten is

the number of inhabitants allotted to each; but some of them now

contain twelve or fourteen, for want of better accommodation. More

are building.

In a cross street stand nine houses for unmarried

women; and exclusive of all these are several small huts where

convict families of good character are allowed to reside.

Of public

buildings, besides the old wooden barrack and store, there is a

house of lath and plaster, forty-four feet long by sixteen wide, for

the governor, on a ground floor only, with excellent out-houses and

appurtenances attached to it.

A new brick store house, covered with

tiles, 100 feet long by twenty-four wide, is nearly completed, and a

house for the store-keeper.

The first stone of a barrack, 100 feet

long by twenty-four wide, to which are intended to be added wings

for the officers, was laid to-day.

June, 1791.

On the second instant, the name of the settlement, at

the head of the harbour (Rose Hill) was changed, by order of the

governor, to that of Parramatta, the native name of it.

December 2nd, 1791. Went up to Rose Hill.

Public buildings here have

not greatly multiplied since my last survey.

The storehouse and

barrack have been long completed; also apartments for the chaplain

of the regiment, and for the judge-advocate, in which last, criminal

courts, when necessary, are held; but these are petty erections.

In

a colony which contains only a few hundred hovels built of twigs and

mud, we feel consequential enough already to talk of a treasury, an

admiralty, a public library and many other similar edifices, which

are to form part of a magnificent square.

The great road from near

the landing place to the governor’s house is finished, and a very

noble one it is, being of great breadth, and a mile long, in a

strait line.

In many places it is carried over gullies of

considerable depth, which have been filled up with trunks of trees

covered with earth.

All the sawyers, carpenters and blacksmiths will

soon be concentred under the direction of a very adequate person of

the governor’s household.

This plan is already so far advanced as to

contain nine covered sawpits, which change of weather cannot disturb

the operations of, an excellent workshed for the carpenters and a

large new shop for the blacksmiths.

It certainly promises to be of

great public benefit.

A new hospital has been talked of for the last

two years, but is not yet begun. Two long sheds, built in the form

of a tent and thatched, are however finished, and capable of holding

200 patients.

Of my Sydney journal,

I find no part sufficiently interesting to be

worth extraction.

This place had long been considered only as a

depot for stores.

It exhibited nothing but a few old scattered huts

and some sterile gardens.

Cultivation of the ground was abandoned,

and all our strength transferred to Rose Hill.

Sydney, nevertheless,

continued to be the place of the governor’s residence, and

consequently the headquarters of the colony.

No public building of

note, except a storehouse, had been erected since my last statement.

The barracks, so long talked of, so long promised, for the

accommodation and discipline of the troops, were not even begun when

I left the country; and instead of a new hospital, the old one was

patched up and, with the assistance of one brought ready-framed from

England, served to contain the sick.

On the 26th of November 1791, the number of persons, of all descriptions, at Sydney, was 1259, to which, 1628 at Rose Hill and 1172 at Norfolk Island be added, the total number of persons in New South Wales and its dependency will be found to amount to 4059.*

[*A very considerable addition to this number has been made since I quitted the settlement, by fresh troops and convicts sent thither from England.]

On the 13th of December 1791, the marine battalion embarked on board His Majesty’s ship Gorgon, and on the 18th sailed for England.

Source:

A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson by Watkin Tench Capt. of the Marines 1791.

A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay Watkin Tench, Capt. of the Marines.

Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, New South Wales, 10 July, 1788.

Watkin Tench, resided at Port Jackson from the 20th of January, 1788, until the 18th of December, 1791.

Governor Philip began a new settlement at Parramatta and before the end of 1790 there were thirty-two houses completed, built of wattles, plastered with clay and thatched.

The image above shows a wattle and daub house similar to the ones constructed at Parramatta. The first church built in Sydney by the Reverend Richard Johnson was a wattle and daub structure with a thatched roof.

Wattle and Daub Hospital in Melbourne demolished by a bull, late 1830s (12)

" Descriptions of the first 'hospital' vary, but agree that it was a totally inadequate hut

of wattle and daub or similar structure, that its two rooms were shared with the constable,

the magistrate and the post office,......"

Source: Cussen, Patrick Edward (1792 - 1849) http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A010260b.htm

" A wattle -and- daub building was put up as a police office,

on the site of the Western Markets, where it did duty for

some time, until one night it fell : some say because it

was undermined by a party of imprisoned natives ; but others,

because a bull belonging to Mr. Batman had rushed against

it."

" Trespass Against a Wall.

Some Legal Definitions,

An old history of Melbourne relates that

the first hospital, constructed of wattle and

daub, was knocked down by a bull

owned by John Batman. The animal

scratched its shoulder against it, and the

building collapsed. According to certain

views expressed in the Full Court of the

High Court yesterday the bull was a trespasser. Had he gently rubbed his nose

against the wall there would probably have

been no trespass.

The Court consisted of

the Acting Chief Justice (Mr. Justice

Isaacs), Mr. Justice Duffy, and Mr. Justice

Clarke.

Argus (Melbourne, Vic.)

Friday 10 October 1924 "

Wattle and daub

The typical English method consisted of vertical rods of hazel sprung into prepared grooves in

the framing, between which thinner rods were woven in and out horizontally to form a basketwork,

and both sides of the basketwork daubed with a mixture of clay, water and straw, sometimes with cow dung. (1)

Wattle and Daub house construction in Australia

Of all the hybrid forms wattle and daub is the best known, at least by repute, and it was used

in the earliest days of Sydney Cove. (1a)

Wattling - that is, the weaving of flexible twigs like

basketwork - was also used in New South Wales without any daub, and this is at least as old

a tradition in Europe.

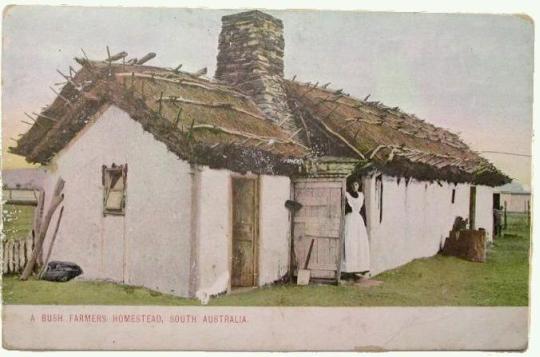

A postcard of a wattle and daub bush farmers homestead in South Australia circa 1900 (21)

Dictionary definition of wattle and daub as described in:

AUSTRAL ENGLISH.

A Dictionary of

Australasian Words, Phrases and Usages

by Edward E. Morris M.A., Oxon. Professor of English, French and German Languages and

Literatures in the University of Melbourne. 1898 (2)

1:

" Wattle-and-Dab, a rough mode of architecture, very

common in Australia at an early date.

The phrase and its

meaning are Old English.

It was originally

Wattle-and-daub.

The style, but not the word, is

described in the quotation from Governor Phillip, 1789.

"The huts of the convicts were still more slight, being

composed only of upright posts, wattled with slight twigs,

and plaistered up with clay." (1)

2: Ross, `Hobart Town Almanack,' p. 66: 1836.

"Wattle and daub. . . . You then bring home from the

bush as many sods of the black or green wattle (acacia

decurrens or affinis) as you think will suffice.

These are platted or intertwined with the upright posts in the

manner of hurdles, and afterwards daubed with mortar made of

sand or loam, and clay mixed up with a due proportion of the

strong wiry grass of the bush chopped into convenient lengths

and well beaten up with it, as a substitute for hair."

3: W. Westgarth, `Australia Felix,' p. 20 1848.

"The hut of the labourer was usually formed of plaited twigs

or young branches plastered over with mud, and known by the

summary definition of `wattle and dab.'"

4: Mrs. Meredith, `My Home in Tasmania,' vol. i. p. 179: 1852.

"Wattles, so named originally, I conceive, from several of the

genus being much used for `wattling' fences or huts. A `wattle

and dab hut is formed, in a somewhat Robinson Crusoe style, of

stout stakes driven well into the ground, and thickly

interlaced with the tough, lithe wattle-branches, so as to make

a strong basket-work, which is then dabbed and plastered over

on both sides with tenacious clay mortar, and finally

thatched."

5: W. J. Barry, `Up and Down,' p. 21: 1879.

"It was built of what is known as `wattle and dab,' on poles

and mud, and roofed with the bark of the gum-tree."

6: J. H. Maiden, `Useful Native Plants,' p. 349: 1889.

"The ordinary name for species of the genus Acacia in

the colonies is `Wattle'. The name is an old English one, and

signifies the interlacing of boughs together to form a kind of

wicker-work. The aboriginals used them in the construction of

their abodes, and the early colonists used to split the stems

of slender species into laths for `wattling' the walls of their

rude habitations."

Early Australian Wattle-and-daub buildings.

In early Australian buildings panels of wattling were sometimes used to close window openings,

and a convict wrote home from Sydney in the first year of settlement of the miserable huts with

windows filled with 'lattices of twigs'. (3)

In the 1820s the verandah of the government hut at

Wallis Creek [Maitland] was temporarily enclosed with panels of wattle to allow a police

contingent to bivouac there (the hut itself being occupied already by the Ogilvie family. (4)

In the Moreton Bay [Brisbane] area in 1824 runaway convicts had built a sort of antecedent

of the bough shed - a shed consisting mainly of a wattled roof supported on eight posts,

measuring 7.2 by 1.8 metres, with the wattling partly thatched over with gum tree branches. (5)

In Sydney even chimneys were made of wattling, leading in 1842 to the issue of a warning about the risk of fire. (6)

The technique would have been known to nearly all British colonists, often directly from their

own experience at home, but more especially from emigrants' handbooks.

Mann's Emigrants Guide to Australia advised in 1849: (7)

" The most usual style of knocking up a house is that called wattle and dab.

Strong uprights of wood are driven into the ground, and long narrow sticks are then woven across these,

like the twigs of a wicker basket. Moist clay, or earth, well mixed up with chopped hay or straw,

is then plastered over this, and finished off with a trowel. The whole is then white-washed inside

and out ... "

In 1837 Thomas Napier built his house in Collins Street - one of the more pretentious

dwellings in the settlement - of wattle and daub with a rush thatched roof. (8)

'Garryowen' [Edmund Finn], describes the method in enough detail to suggest that he really was

familiar with it in the local context: (9)

"... the size of the required 'premises' was to be marked, and stakes or posts to be driven into

the ground a few feet apart: these were then connected with interwoven twigs of gum, wattle or ti-tree,

like rough wickerwork. The next stage was to 'daub' well on both sides with kneaded clay, and

so puddled, when bakes in the sun, the walls became weatherproof. After roofing of bark, reeds,

or shingle was attached, if there were the addenda of a brick chimney, and a dash of whitewash

externally, the habitation or store, as the case may be, was considered complete. "

John McKimmie of Bundoora, north of Melbourne, spoke of a daub made from clay and cow dung,

the same mixture as was used for flooring. (10)

A regulation style Wattle and Daub House

Wattle and doub house.

Image courtesy of: State Library New South Wales http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/

The construction of a regulation style wattle and daub house according to the American adventurer Gus Peirce who arrived in Hill End in 1871.

" This house was constructed in regulation style, without sills, by simply driving saplings into the ground at regular intervals, on either side of which were fastened the wattles or split limbs, forming horizontal half-rounds, the space between them being filled in solid with a mixture of earth, water, and grass. The roof was made of saplings and gum bark, and a chimney erected of slabs and finished with a barrel. A trench was then dug around the hut to drain off the water, and the new residence was complete. " (16)

The Shortage Of Good Mortar.

The prevalence of single storey

buildings in early Sydney, as well as their rapid rate of deterioration can be attributed to the shortage of good mortar.

Governor Phillip said.

" the materials can only be laid in clay, which makes it necessary to give great

thickness to the walls, and even then they are not so firm as might be wished. ".

Brick

walls were built with mortars of clay or loam at Government House, Parramatta,

1790, and at John Macarthur's Elizabeth Farm 1793.

Lieutenant-Governor David Collins was particularly unfortunate, the house built for him on the western side of the Tank Stream lacked the necessary amount of lime and " gave way with the heavy rains and fell to the ground ".

The Tank Stream Sydney (17)

Loam was also used for plastering.

Neither limestone or chalk was to be found in the vicinity of Sydney Cove, and

shells were burnt for lime in the first months of settlement.

Governor Phillip is said to have

brought a little lime from England to the settlement, but he had to try and obtain more

locally even for his own house.

" The Governor ", wrote John White, " notwithstanding

that he had collected together all the shells which could be found, for the purpose of

obtaining from them the lime necessary to the construction of a house for his own

residence, did not procure even a fourth part of the quantity which was wanted. "

Such lime as could be obtained from sea shells at Sydney was in great demand for

stuccoing and plastering over the other inferior building materials, and not much was

used for mortar or other structural purposes.

As a general rule shells can be easily seen in the mortar of older buildings in coastal

and riverine New South Wales.

Shell lime was burnt from the piles of oyster shells

found in Aboriginal middens all along the coast,

" These proved a valuable resource to us, and many loads of shells were burnt into lime...(20) ", and when these were exhausted the

bays and inlets were dredged for live oysters.

In the 1850s and 1860s the activities

of the shell diggers had become a problem in the Sydney region, and were resulting in

the depletion of oyster supplies, a problem overcome only when the establishment of

railway connections in the 1870s enabled rock lime to be brought from inland.

Animal hair such as horse hair was sometimes mixed in the mortar, or human hair if necessary.

In 1832 it was

reported that four hundred convicts were being shorn at Norfolk Island to provide hair

for the purpose.

Partially Referenced from. Cement & Concrete: Early Lime & Cement:

Early settles hut in the Wielangta Forest, Tasmania

Photo courtesy http://www.bairdnet.com/australia.html

The first detailed description of a Bark

Hut in Australia: 1822

" Some stakes of trees are stuck in the ground, the outside bark from the trees is tied

together, and to these with narrow strips of what is called stringy bark; being tough, it

answers the purpose of cord, and the roof is done in the same manner.

There was a kind of chimney but neither window nor door, but a space left to enter. "

Source. 'Journey from Sydney to Bathurst in 1822' Elizabeth Hawkins

Construction of an Australian

bark hut. 1826

One of the earliest descriptions of the construction of an Australian

bark hut is that by James Atkinson in 1826

" ...this is effected by setting up corner posts of saplings, surmounted by plates, and the

frame of a roof of small poles.

Some large sheets of the bark of the box or stringybark

are then procured; some are set on their ends to form the sides, and others laid

up and down on the top to form the roof, with one or two long pieces lengthways to

form the ridge, securing the whole by tying it with strips of the inner bark of the stringy

bark; a space is left for a door, and a square hole cut for a window, and pieces

provided to close these apertures at night; some long pieces are then built into the

form of a chimney at one end, and sods placed inside to prevent their catching fire.

Care is taken to give the different sheets sufficient overlap to allow for their shrinking,

and also to give the eaves sufficient projection to carry the rain water from the walls;

a trench is dug round to carry off the wet ... "

Source. Atkinson, Agriculture and Grazing in

New South Wales, 1826. pp 29-30.

The Aborigines were indeed important in showing the

settlers how to strip bark and which species to use. However, the Aborigines lacked the

technology to cut bark on a large scale until the European tomahawk became available.

An early indication of direct transference from the Aboriginal to the European culture of the

idea of using bark occurs in Dawson's account of the Aboriginal contribution in 1826.

" As soon as we had raised the frames of some our

intended habitations, we were sadly at a loss for bark to close the sides and

cover the roofs. " Seeing their plight, a local Aboriginal brought a dozen of his fellow

tribesmen to assist.

" having received each a small hatchet, set to work in good earnest, and brought such a

quantity of bark in two or three days as would have taken our party a month to

procure. Before a white man can strip the bark beyond his own height, he is obliged

to cut down the tree; but a native can go up the smooth and branchless stems of the

tallest trees, to any height, by cutting notches in the surface large enough to place the

great toe in, upon which he supports himself, while he strips the bark quite round the

tree, in lengths from three to six feet. These form the temporary sides and coverings

for huts of the best description. "

Source: Robert Dawson, The Present State of Australia [London 1830], pp 19-20.

A less satisfactory transaction between the races occurred

when 'Cocky' Rogers, superintendent of 'Grantham' station in what is now Queensland,

simply helped himself to four hundred sheets of bark from Aboriginal humpies, with which to

roof his store sheds and huts.

Source: Steel, Brisbane Town in Convict Days, p 299.

An extract from: " AN EMIGRANT'S ADVENTURES " 1820

A little hut by the road-side.

" The hut itself, which was merely a few sheets of

bark stripped from trees, and each varying from

the size of a common door to that of double that

width by the same length, was but a single area

of about nine feet one way by six the other; the

roof, too, was of bark, and of the usual shape.

One of the six-feet ends was a chimney, through

out its whole width, in which the fire was made

by logs of any length and thickness available.

On the earthen hearth, at the other six feet end,

was a sort of berth, also of bark, like the bunks

on board ship, fixed at about three feet from the

ground; whilst at the nine feet side next the road

was the door, which likewise was of bark; and at

the opposite parallel side was a little table, and

that too was of bark, to wit, a sheet about three feet one way by two the other, nailed on to four

little posts driven into the ground, and having

of course its inner or smooth side upwards.

The architect of the building had used all his

materials whilst green, so that in seasoning they

had twisted into all manner of forms except

planes and as is usually the case, the worst

example came from the most responsible quarter;

the table was the crookedest thing in the whole

hut, not excepting the dog's hind leg.

Standing

about the floor were sundry square ended round

blocks of wood, just as they were first sawn off

the tree transversely , they were each about

eighteen inches long, and their official rank in

the domestic system was equivalent to that of

the civilized chair.

After a good supper of hot fried beefsteaks,

damper bread and tea, which our host, a free

hearted, hardworking bushman, gave with many a

"Come, eat, lad; don't be afraid; there is plenty

more where this came from," etc., etc., according

to the custom of the colony and especially of his

class, we betook ourselves to a smoke of good old

Brazil, over the latter part of our quart pots of tea;

and then at nearly two o'clock my companion re

minded his brother that it was " time to pig down."

Accordingly our entertainer, clearing the floor

by making us stand in the chimney, putting the

blocks under the table, and giving his dog a

kick, which I thought the thing least to his credit

that I had seen him do, began to " make the

dab."

This was accomplished by stretching his own

bed, which was only adapted for a single person,

lengthwise across the hut, at about six or seven

feet from the fire place; then lying down across

the hut in the same manner between the bed and

the fire place all the old clothes he could muster

of his own; and finally over these he spread about

half a dozen good-sized dried sheepskins with the

wool on.

These, with a blanket spread over the

whole, really made a very tolerable bed. Certainly towards morning I began to feel a good deal

as if I were lying with my body in a field and my

legs in the ditch beside , however, I have had

many a worse lodging between that night and

this. "

Our hosts were two Irishmen, brothers.

" The hut was well built of slabs split

out of fine straight-grained timber, with hardly

a splinter upon them; and consisted of several

compartments, all on the ground floor.

The

only windows were square holes in the sides of

the hut, and a good log fire was blazing in the

chimney.

On stools and benches and blocks

about the hut sat a host of wayfarers like ourselves,

and several lay at their ease in corners on their

saddle cloths or blankets, whilst saddles and packs

of luggage were heaped up on all sides.

Supper

was over, and the short pipes were fuming away

in all directions. Our hosts were two Irishmen,

brothers, who had got a little bit of good land

cleared here in the wilderness, and refused nobody

a feed and shelter for the night.

They soon put

down a couple of quart pots of water before the

blazing fire, made us some tea, and set before us

the usual fare, a piece of fine corned beef, and a

wheaten cake baked on the hearth. "

Source: Settlers and Convicts - Recollections of Sixteen Years Labour in the Australian Backwoods.

Alexander Harris (1805-74)

A Sketch of the interior of a Settler's Hut 1849

" The Sketch of the Settler's Hut from

the pencil of Mr. Skinner Prout represents an Australian dwelling, of a class commonly met with in the

Bush.

It is constructed of rudely split logs placed upright in the ground, the interstices being in

most cases filled up with mud or clay; but the peculiar circumstance connected with the Hut here drawn

was this:--

On one of his sketching excursions our Artist was anxious to cross some mountain tiers, in order to

make a straight line to a spot he was

anxious to visit at some twelve miles distant.

He was aware that there was no marked road; and that to

attempt it without a guide would be

to run a serious risk of losing himself in the intricacies of the wild forest with which the country is

covered.

However, he very soon had the

gratification to reach a clearing, and to see, a few hundred yards before him, a column of bright blue

smoke rising among the gum-trees, and

indicating the hut of some settler.

Australian hospitality has become proverbial, and,

says Mr. Prout,

" perhaps few persons have experienced it more frequently than myself.

My wanderings as a sketcher have often led me among scenes and in situations where I have been

wholly dependent on such sources for food and shelter; and I have ever received it with a

hearty good-will, and in such a manner as one might have inferred that I had been rather the

dispenser than the recipient of such kindness.

It was just so, at the time to which I have

alluded. I made my wants known, and a young man who was the shepherd on the station offered to

become my guide.

This matter being settled, the iron pot was placed on the fire, and a plentiful repast of mutton chops

and sassafras tea prepared us

for our journey; but before we started, my friend 'Joe' must have his pipe, and I must have my sketch.

The interior of the little hut presented so quiet, so enticing a bit, that I must needs make a

memorandum of it. Joe had smoked himself into a state of semi-dreaminess,

and seated on a log of wood, displaying an attempt at the formation of a chair, was contemplating

with a most thoughtful visage a large posting bill. an advertisement of the ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS,

announcing the Queen's visit to Drayton Manor, &c. Doubtless, dreams of greatness, and thoughts

of home, were passing through the poor shepherd's mind: he appeared quite lost in thought, and in

imagination was far, far away from the wilds of Australia; but his kangaroo dog, which had been

lying at his feet, roused himself, disturbed his master's reveries, and at the same time afforded me

an intimation that it would be well to commence our journey."

How the posting-bill, announcing the Visit of Queen Victoria to the Midland Counties of England, had found its way into the Settler's Hut,

we are not informed; but there our Artist witnessed the affiche, treasured as a picture." (19)

An extract from: " Australian Life, Black and White " 1885

The stockman's hut.

Each stockman's hut stood by itself in a clearing, leagues distant from any other dwelling, and as far as might be from the nearest scrub, in the thickets of which the Blacks could always find an unassailable stronghold.

The hut was built of logs and slabs, the roof of bark; the fireplace was a small room with a wide wooden chimney. Shutters there were, and a door, but locks were unknown, and bolts and bars were of the most primitive description.

The settler depended for safety upon the keenness of his hearing, the excellence of his carbine, and the Blacks' superstitious dread of darkness, which makes them averse to leaving their camp except on moonlight nights, or with an illumination of burning firesticks.

Naraigin Sheep station. circa 1850's

Naraigin was a station in one of the most unsettled districts--on the very borders of unexplored country, of which my father took possession when I was about seven or eight years' old.

A queer one-storied hut, built of slabs which had shrunk apart, so that there were wide gaps everywhere, with a sloping roof of bark and a wide and roughly boarded verandah.

Windows there were none, that is to say in the sense of panes of glass , there were wooden shutters that could be closed at night.

Most of the floors were earthen; I think the sitting-room was boarded, but am not sure. The rooms were unceiled, and I have a vivid recollection of uncanny looking white lizards and bloated tarantulas which abode beneath the rafters.

There was a kitchen behind, connected with the house by a covered passage; and there were other outbuildings--a meat store, on the roof of which the bullock hides were stretched to dry, and a wool-shed some little distance away, which with its many pens, its empty wool bales, and presses, its odd holes and corners, was the most delightful playing-- ground imaginable.

Then there was a garden, fenced in with hurdles, over which our tame kangaroo took his daily constitutional; but nothing grew in

it except pumpkins and fat-hen. Well for us that they did flourish, for we lived on pumpkins and mutton for three months, during which time the drays

were delayed by flooded creeks, and the store was empty of flour, tea, sugar, and all other groceries. "

Source: Australian Life, Black and White by Rosa Praed 1885

Rosa Praed.

Rosa's father, Thomas Lodge Murray-Prior, had arrived in New South Wales in 1839 at the age of 19. A handsome 'ladies' man' and 'a gentleman squattah who drove his own [bullock] team'.

He married the Anglo-Irish emigré, Matilda Harpur, in Sydney in 1846.

Third born of this union, Rosa Caroline 's most formative early childhood years were spent on the frontier outpost of European settlement, Naraigin, on the Auburn River 300 km north-west of Brisbane where the town of Hawkwood now stands.

Source: http://www.emsah.uq.edu.au/awsr/recent/131/r.html

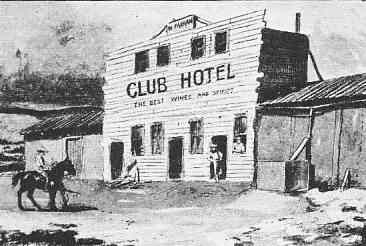

September, 1892

" As recreation we used to play occasional games of cricket on a very hard and uneven pitch, and for social entertainments had frequent sing-songs and “buck dances”—that is, dances in which there were no ladies to take part—at Faahan's Club Hotel in the town,

“Hotel” was rather too

high-class a name, for it was by no means an imposing structure, hessian and

corrugated iron taking the place of the bricks and slates of a more civilised

building.

The addition of a weather-board front, which was subsequently erected,

greatly enhanced its attractions. Mr. Faahan can boast of having had the first

two-storeyed house in the town; though the too critical might hold that the upper

one, being merely a sham, could not be counted as dwelling-room.

There was no

sham, however, about the festive character of those evening entertainments. " David W Carnegie (1871-1900)

A Narrative of Five Years' Pioneering and Exploration in Western Ausralia

HON. DAVID W CARNEGIE (1871-1900)

Descriptive Sketch of Victoria circa 1860.

" The first settlers endured the inclement climate and the harshness of the bush as they went forth into the forest with the manly determination to reclaim the wilderness and to make themselves a home in its previously unbroken solitudes. To do this, has involved no small amount of courage, of patient endurance, of steadfast hope, of physical strength and of pertinacious toil.

Most of the selector’s capital consists of these admirable qualities, for his stock of ready money is usually exhausted by the time he has ringed and felled a few trees upon the site of his future homestead, erected a hut of slabs and bark, furnished it with a trestle bed and blankets, a rudely-constructed table and bench, a few cooking utensils, an axe, a spade, a crosscut saw, and a supply of flour, tea and sugar.

He knows that he must "shun delights and live laborious days," and when he has broken up a few perches of land and put in his first crop, he is not unfrequently compelled to seek for work in the neighbourhood at fencing or road-making, in order to maintain himself until the "kindly earth" shall have yielded him her increase.

In some cases the free-selector, who is fortunate enough to be the possessor of a horse and to be quick and dextrous in the use of the shears, sets out in the beginning of August for the woolsheds in the south of Queensland, or in the north of New South Wales, to fulfil a yearly engagement at sheep-shearing, and makes his way downward from station to station, through Riverina and the Murray country into Victoria, returning in time to gather in his own crops, and with cheques in his pocket representing at least a hundred pounds.

Wattle and daub home with bark roof and parget wooden chimney.

He is thus enabled to purchase a few head of stock or a better description of plough, to build a more commodious hut, and to supply the wife and children, for whom he has been making a home in the bush, with such articles of wearing apparel as they may stand in need. There is plenty of hard work and very little recreation in such a life, and the most lively imagination would fail to invest its prosaic realities with a halo of romance or with an air of poetry. "

Description of the erection of a bush hut in Gippsland in the 1860's:

" The timber on the Gipp's Land hills is free splitting.

The kind mostly used for

splitting purposes is the stringy bark, so called from the facility with which it can be

stripped or pulled into strings, and the fibres of which can be twisted into ropes for

houses.

The method of barking the tree is to ring it at the butt, and again eight or nine feet above, then split it down from one girdle to the other, get the fingers in

and start it from the wood. When once started, it will readily peel around the body

of the tree, and come off one whole sheet, eight feet long and from three to six feet

wide.

Take a long-handled shovel and strip off the round outside bark, and it will

resemble a side of sole leather. Two men can strip from forty to sixty sheets in a

day, so it did not take long to strip enough bark to cover a house, sides, roof and all.

The young stringy bark trees make the best of poles, and one can cut them twenty five

or thirty feet long, as straight as a candle, and, if desired, not more than three

inches in diameter. Two men can go into the bush and strip the bark, cut the poles

and put up a house inside of a week, and a good tidy-looking one too, and such a

one as many thousands who are worth their thousands of pounds have lived in for

years. "

Source: C D Ferguson [ed F T Wallace], The Experiences of a Forty-Niner during Thirty Four Years

Residence in California and Australia (Cleveland [Ohio] 1888), pp 469-70.

Photo courtesy http://www.bairdnet.com/australia.html

Adobe or mud brick construction mid 1800's

Adobe or mud brick construction developed

from the mid 1800s,

the Southern Australian reported in 1839 of this form of construction: nearly thirty houses have been

erected, they are mostly built of pisé , or of unburnt bricks, which have been hardened by the sun.

With the increase in availability of baked bricks and milled timber it became less common and

was mostly restricted to remote rural areas

Note the Bicycle resting against the wall under the right window.

A new bicycle costs about $31.00 ($1,550.00 at todays prices) the equivalent of more than seven weeks wages.(13)

Data sourced from: Earth Building Research Forum at the University of Technology, Sydney

Perception of a pisé house as described in the novel :

Tales of the Colonies

by Charles Rowcroft.(14)

"Come, give us your advice about a pisé house, as you have seen some of

them and I have not; will they do?"

"Do! Lord bless you--never think of making a mud-pie and calling it a

house. Who ever heard of patting mud up into a heap, and then setting a

roof on it? Why, it must crumble to pieces, or be washed away by the

first rain that comes. But why talk of a mud house when you have plenty

of stone on your own land?"

Charles Rowcroft (1798–1856), arrived in Hobart in 1821 and took up a large land grant near Bothwell.(15)

1901 Census of Australian Dwellings and their type of construction.

In 1901, 786,331 dwellings were counted.

Of these dwellings, 459,558 (58.4%) were made from Wood, Iron, Lath & Plaster, Slab, Bark, Mud, etc, 266,246 (33.8%) were made from Stone, Brick, Concrete, etc; and 42,967 (5.6%) were made from Calico, Canvas etc.(a)

In the 2001 Census, there were a total of 7,072,202 occupied private dwellings comprising 5,327,309

separate houses (75.3%), 632,176 semi detached,

row or terrace houses and townhouses (8.9%), 923,139 flats, units or apartments (13.1%) and 134,274 other dwellings (1.9%).(b)

Footnote (a) Dwellings under construction have been included in dwelling counts. The categories of materials have been grouped to provide comparable categories across states. The category "Wood, Iron, Lath & Plaster, Slab, Bark, Mud etc" includes wattle, dab and metal. The category "Stone, Brick, Concrete etc" includes adobe and pise. The category "Calico, Canvas etc" includes linen, tents, drays and hessian.

Footnote (b) The 2001 results are for occupied

private dwellings only.

Materials Used in Dwellings | |||||

Wood, Iron, Lath, Bark Plaster, Slab | Stone, Brick, Concrete etc. | Calico, Canvas, Tents. | Not Specified | Total | |

| New South Wales | 150,814 | 105,197 | 8,874 | 3,886 | 268,771 |

| Victoria | 169,252 | 75,696 | 3,423 | 5,285 | 253,656 |

| Queensland (a) | 83,634 | 2,548 | 9,609 | 4,819 (a) | 100,610 |

| South Australia | 12,258 | 61,279 | 1,564 | 753 | 75,854 |

| Western Australia | 18,380 | 13,467 | 18,628 | 495 | 50,970 |

| Tasmania | 25,220 | 8,059 | 869 | 2,322 | 36,470 |

| Total AUSTRALIA | 459,558 | 266,246 | 42,967 | 17,560 | 786,331 |

Note: In 1901, New South Wales included the area now known as the Australian Capital Territory. Figures for South Australia included the Northern Territory.

Data Source: 1901 State Censuses (Census of Queensland 1901, South Australian Census 1901, Census Western Australia 1901, Census of Victoria 1901, Census New South Wales 1901, Census of Tasmania 1901).

Source: 2001 Census of Population and Housing - 00 1901 Australian Snapshot:

Australian Bureau of Statistics.

http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/d3310114.nsf/Home/Home?OpenDocument

An exhibition from the NSW State Cultural Institutions:

Built for the bush: green architecture of rural Australia looks at traditional sustainable principles

used in architecture from the early days of British settlement and discusses how they are applied to

environment and become more sustainable designers of products and homes.

View Historic Houses Trust: http://www.hht.net.au/

Secondary Teacher notes.

http://www.hht.net.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/43957/Stage_4,_5_and_6_Education_Kit.pdf

Stage 2 & 3 Education Kit.

http://www.hht.net.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/43958/Stage_2_and_3_Education_Kit.pdf

Other Articles

1: Early Settlers in Victoria Australia.

2: Drought and Bush Fires in Victoria 1851 Black Thursday.

3: Chronology of Australian Major Bush fires.

4: Chronology of Australian Major Droughts.

5: Archaeological site at Mount William Stone Hatchets.

6: Megafauna bones found at Lancefield - Giant Kangaroo.

7: Is there a risk of a volcanic eruption in Australia ?

References and other Sources:

(1) Cook, English Cottages and Farmhouses, p 14.

(1a) Arthur Phillip, Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay (London, 1789), p 145.

(2) A Dictionary of

Australasian Words, Phrases and Usages

by Edward E. Morris M.A., Oxon. Professor of English, French and German Languages and

Literatures in the University of Melbourne. 1898

(3) Historical Records of New South Wales, I, part II, p 747, quoted in John Archer, Building a Nation (Sydney 1987), p 28; or Historical Records of New South Wales, II, appendix I, British Museum Papers, pp 746-9, as quoted in Helen Heney [ed], Dear Fanny (Rushcutters' Bay [New South Wales] 1985, p 1.

(4) George Farwell, Squatter's Castle (Melbourne 1973), p 54.

(5) Allan Cunningham, Journal 1822-31, S29, New South Wales Archives Office, 9 July 1827, 'Report of Observations made during the progress of a late Tour between Liverpool Plains and Moreton Bay', quoted in Ian Evans et al, The Queensland House: History and Conservation (Mullumbimby [New South Wales 2001)

(6) Sydney Gazette, March 1804, quoted in John Archer, Building a Nation (Sydney 1987), p 32.

(7) Mann's Emigrants Guide to Australia (London 1849), p 23, cited in Michael Pearson, Notebook on Earth Buildings, p 31.

(8) F J Wilkin, Baptists in Victoria: Our First Century 1838-1938 (Melbourne 1939), p 9.

(9) 'Garryowen' [Edmund Finn], The Chronicles of Early Melbourne 1835 to 1852 (2 vols, Melbourne 1888),

(10) Len Kenna, In the Beginning there was the Land (Bundoora [Victoria] 1988), p 34.

(11) Image source Native Village in the northern interior. 1847

NARRATIVE OF AN EXPEDITION INTO CENTRAL AUSTRALIA PERFORMED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HER MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT,

DURING THE YEARS 1844, 5, AND 6,

TOGETHER WITH

A NOTICE OF THE PROVINCE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA IN 1847.

IN 2 VOLUMES.

By Capt. CHARLES STURT, 39th Regt. F.L.S. and F.R.G.S.

(12) Date of the incident presumed to have occurred in the late 1830s

A short history of The Royal Melbourne Hospital

http://www.mh.org.au/Royal_Melbourne_Hospital/www/353/1001127/displayarticle/history-of-rmh--1001564.html

(13) Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. http://www.abs.gov.au/

(14) TALES OF THE COLONIES

or, THE ADVENTURES OF AN EMIGRANT

EDITED BY A LATE COLONIAL MAGISTRATE.

LONDON

SAUNDERS and OTLEY

In Three Volumes.

FIRST PUBLISHED: 1843

ROWCROFT, CHARLES (1798-1856)

(15) Source: Hand made homes

http://blog.sl.nsw.gov.au/holtermann/index.cfm/2009/10/2/hand-made-homes

http://blog.sl.nsw.gov.au/holtermann/index.cfm/2010/1/22/guss-excellent-adventure

(16) Source: Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies

http://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/R/Rowcroft.htm

(17) Image Source: The Tank Stream Sydney. The Coming of the British to Australia

1788 to 1829 by Ida Lee (Mrs. Charles Bruce Marriott) LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK AND BOMBAY

1906

(18) Source: An Account of the English Colony of NSW Vol 1

by

David Collins Esquire Late Judge Advocate and Secretary Of The Colony.

1798

(19) Source: Bound volume of the Illustrated London News January to June 1849

Image source. A bush hut of slabs and bark circa 1860

"Picturesque Atlas of Australasia" a three-volume geographic encyclopaedia of

Australia and New Zealand compiled and published in 1886.

Descriptive Sketch of Victoria

(20a) Source: Aboriginal Housing Construction.

http://www.aboriginalculture.com.au/housingconstruction.shtml Accessed 12/12/2010

(20) Source: Aboriginal Housing.

http://www.aboriginalculture.com.au/housing.shtml Accessed 12/12/2010

(21) Source: Aboriginal culture. Traditional Life

http://www.aboriginalculture.com.au/housing.shtml Accessed 01/05/2010

(22) Image: Dome sweet dome ... a shelter in western Victoria from 1847. Source: Gunyah, Goondie + Wurley: The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia.

Further Reading:

• Australian Building: A Cultural Investigation by Professor Miles Lewis.

- University of Melbourne Website: http://mileslewis.net/australian-building/

• Australian Children’s Televsion Foundation Website: http://www.actf.com.au/education

• Australian Children’s Televsion Foundation Website: http://www.actf.com.au/news/story/10030

• My Place for Teachers [Episode 22 | Milking time] Student Activity 2: Home sweet home Website: http://www.myplace.edu.au/teaching_activities/1878_-_before_time/1798/2/milking_time.html

• Garryowen (E. Finn), Chronicles of Early Melbourne, vols 1-2 (Melb, 1888)

• Memmott, Paul, Gunyah, Goondie + Wurley: The Aboriginal architecture of Australia, University of Queensland Press, 2007.

• Basedow, Herbert, The Australian Aboriginal, Preece, Adelaide, 1925.

• Australian forest profiles: Acacia - http://www.daff.gov.au/brs/publications/series/forest-profiles/australian_forest_profiles_acacia

• An Account of the English Colony of NSW Vol 2

by

David Collins Esquire Late Judge Advocate and Secretary Of The Colony.

1882

Romsey Australia, 'Early settlers' homes and bush huts in Australia', is cited for further reading at:

• Australian Children’s Televsion Foundation

Website: http://www.actf.com.au/

• Education Services Australia

Website: http://www.esa.edu.au/

• Historic Houses Trust:

Website: http://www.hht.net.au/

• Secondary Teacher notes.

Website: http://www.hht.net.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/43957/Stage_4,_5_and_6_Education_Kit.pdf

Early Settlers Homes and Bush Huts in Australia. ( 32 pages )

by Romsey Australia is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Australia License.

Revised 01/01/2018