The Wurundjeri, a sub-group of the Woiworung, quarried greenstone at Mount

William near Lancefield 10 km north of Romsey and 78 km from Melbourne, Australia,

to make hatchet blanks.

The Wurundjeri, a sub-group of the Woiworung, quarried greenstone at Mount

William near Lancefield 10 km north of Romsey and 78 km from Melbourne, Australia,

to make hatchet blanks.

Although we do not know exactly when this started it must

have been sometime in the last 1,500 years, the period during which

Aboriginal people in south-east Australia used greenstone hatchets. (1).

During this period Aboriginal people in

eastern Australia relied on ground-edged stone hatchets as a general purpose tool used in

a variety of ways: to cut open the limbs of trees to get possums from hollows; to

split open trunks to get honey or grubs or the eggs of insects; to cut off sheets of bark

for huts or canoe; to cut down trees; to shape wood into shields or clubs or spears;

and, to butcher larger animals.

Unlike many other utilitarian Aboriginal stone tools ,

ground-edged stone hatchets, especially those from important quarry sites, were

traded over long distances. They were treated as valued items, with prestige attaching to

their owners. The trade in stone hatchet heads therefore created social links and

obligations between Aboriginal groups.

During the late Holocene, as woodlands expanded, ground-

edged stone hatchets became an essential part of the

Aboriginal toolkit in eastern Australia.

They were an

important all-purpose tool as well as being an item of

prestige.

Material for these tools was obtained from specific

quarries.

The Mount William stone hatchet quarry.

The Mount William stone hatchet quarry was an

important source of stone hatchet heads which were traded

over a wide area of south-east Australia.

The quarry area has

evidence for both surface and underground mining, with 268

pits and shafts, some several metres deep, where sub-surface

stone was quarried (McBryde & Watchman, 1976:169).

There are 34 discrete production areas providing evidence for

the shaping of stone into hatchet head blanks. Some of these

areas contain mounds of manufacturing debris up to 20

metres in diameter.

At Mount William, the number, size and

depth of the quarry pits; the number and size of flaking floors

and associated debris; and the distance over which hatchet

heads were traded is outstanding for showing the social and

technological response by Aboriginal people to the expansion

of eastern Australian woodlands in the late Holocene.

Stone Hatchets and Aboriginal Quarrying During the late Holocene.

As woodlands expanded over much of Eastern Australia,

Aboriginal people in these areas adopted and relied on ground-edged stone hatchets as a general purpose

tool used for a variety of tasks: to cut open the limbs of trees to get possums from hollows; to split

open trunks to get honey or grubs or the eggs of

insects; to cut off sheets of bark for huts or canoe; to cut down trees; to shape wood

into shields or clubs or spears; and, to butcher larger animals.

As woodlands expanded over much of Eastern Australia,

Aboriginal people in these areas adopted and relied on ground-edged stone hatchets as a general purpose

tool used for a variety of tasks: to cut open the limbs of trees to get possums from hollows; to split

open trunks to get honey or grubs or the eggs of

insects; to cut off sheets of bark for huts or canoe; to cut down trees; to shape wood

into shields or clubs or spears; and, to butcher larger animals.

The importance of this

tool to Aboriginal people in eastern Australia is reflected by the fact there was at least

one stone axe in every camp, in every hunting or fighting party, and in every group travelling

through the bush.

The

importance of ground edged stone hatchets was not confined to the utilitarian; they were also

valued trade items that extended the range of social relationships well

beyond the local group. Ethnographic records indicate that such exchanges were

usually embedded in the regional network of prestige, marriage and ceremonial activity

While ground-edge stone hatchets

can be produced from a range of raw materials

including river cobbles, the best raw materials occur in relatively few places and material suitable

for ground-edged hatchets was extracted from specific quarry

locations selected for the suitability of the material for its use for cutting, scraping,

pounding and chopping (Mulvaney & Kamminga, 1999:213).

A number of quarries

used to obtain material for ground stone hatchet head production are known. These

include Moore Creek in northern New South Wales, Lake Moondarra in Queensland Mount Camel in Victoria.

There are, however, only a few quarries that were

intensively worked and the stone hatchet heads from these quarries were traded over long distances.

The ground stone hatchet heads and the quarries from which they

were obtained are the product of social and technological adaptations by Aboriginal people in response

to the expansion of woodlands during the late Holocene.

Historical accounts

of the Mount William quarry.

William Buckley, an escaped

convict living in the bush from 1803 to 1833 provides

the earliest European reference to the Mount William quarry, describing a hard, black stone from a place

called Kar-keen which was shaped into stone heads. (2)

William Buckley, an escaped

convict living in the bush from 1803 to 1833 provides

the earliest European reference to the Mount William quarry, describing a hard, black stone from a place

called Kar-keen which was shaped into stone heads. (2)

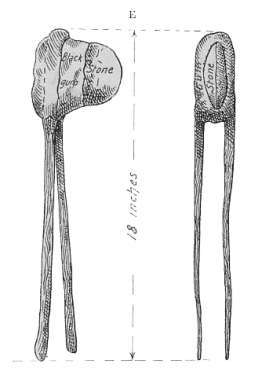

The image above represents a Greenstone Axe blank (left) and Ground-edge Axe (right) (3)

Characteristics of ground-edge stone axes.

• Ground-edge axes come in different shapes, but they are usually either round or oval. They are sometimes rounded and narrow at one end, and slightly broader and straighter at the cutting edge.

• Most are 50–200 millimetres long, 40–100 millimetres wide and 20–60 millimetres thick.

• Typically they are ‘lens shaped’ when viewed from the side.

• They were made from hard types of stone, particularly basalt or greenstone, and worn river pebbles.

• They may have one or more ground cutting edges, and they may be polished smooth all over. The ground surfaces are usually highly polished.

• They may have a groove pecked around their ‘waist’ so it is easier to attach a handle.

William von Blandowski, the first zoologist

at the Melbourne Museum, visited Mount William in 1854 (Blandowski, 1855:56) and provides this account

of the quarry.

"The celebrated spot which supplies the natives with stone (phonolite) for their tomohawks, and of which I

had been informed by the tribes 400 miles

distant. Having observed on the tops of these hills a multitude of fragments of stones which appeared

to have been broken artificially.

Here I unexpectedly found the

deserted quarries (kinohahm) of the aboriginals.

The quarries extend over an area

of upwards of 100 acres . They are situated midway between the territories of two

friendly tribes, - the Mount Macedon and Goulburn, - who are too weak to resist the

invasion of the more powerful tribes; many of whom, I was informed, travel hither several hundred of

miles in quest of this invaluable rock. The hostile intruders,

however, acknowledge and respect the rights of the owners, and always meet them in peace" (4)

McBryde's archaeological research on the distribution of Mount William hatchets shows that the

Aboriginal exchange networks for Mount William stone hatchets

extended several hundred kilometres (McBryde, 1978:355). Her analysis of the

distribution of these items provide evidence that some stone hatchets were exchanged from

secondary centres and demonstrated that the distribution of Mount William stone hatchets

reflected social and political relations.

Not all hatchet heads came from Mount William, although that quarry was probably the most important in the region. Outcroppings of silcrete, which was favoured for making small flaked implements, are known to occur in the Keilor area and on the Mornington Peninsula.

Ground-edged Stone Hatchet—from Sturt Creek ( Western Australia )

The head is of a very dark and hard green stone, ground to a fine edge, and is set between the two arms of the handle and held in place with spinifex gum. The handle is formed by bending round

(probably by means of fire) a single strip of wood. The two arms of the handle are sometimes held together by a band of hair-string. Source: Spinifex and Sand by David W. Carnegie A Narrative of Five Years' Pioneering and Exploration in Western Ausralia 1892

References and other Sources:

(1) McBryde, I (1984b). Kulin greenstone quarries: The social contexts of production and distribution for the Mount William site. World Archaeology 16(2): 267-285.

(2) Brough Smyth, R. (1876). "The Aborigines of Victoria: with notes relating to the habits of the natives of other parts of Australia and Tasmania" and compiled from various sources for the Government of Victoria. Melbourne: John Currey, O’Neil

(3) Source and image courtesy of: Aboriginal Ground-edge Axes.

Website: www.dpcd.vic.gov.au/aav File: aa_08_groundaxes_13.06.08.indd.pdf

(4) Blandowski, W von. (1855). Personal observations made in an excursion towards the central parts of Victoria, including Mount Macedon, McIvor and Black Ranges. Transactions of the Philosophical Society of Victoria. Vol. 1, 50-74

Image Source: Australian Aborigine Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia, Vol 2 (of 2), by Thomas Mitchell.1836

ColourImage Source: Stone Hatchet Grinding stone were adapted and modified from: Courtesy Hogarth Arts Weapons http://www.hogartharts.com.au/weapons.htm

Reference: Coutts, P.J.F. & Miller, R (1977). The Mt. William archaeological

Victorian Archaeological Survey, Government Printer

Reference: McBryde, I (2000). Continuity and discontinuity: Wurundjeri custodianship of Mt William quarry. In S Kleinert and M Neale (eds.) The Oxford companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture (pp. 247-251). Melbourne: Oxford University Press

Reference: Australian Heritage Database National Heritage List Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry Place ID:105936 File No:

2/06/078/0002

Reference: Spinifex and Sand by David W. Carnegie A Narrative of Five Years' Pioneering and Exploration in Western Ausralia 1892

Further Reading:

Andrews, E.C., 1911, Report on the Cobar Copper and Gold-Field, New South Wales Department of Mines, Geological Survey, Sydney

Flood, J., 1983, Archaeology of the Dreamtime, William Collins Pty Ltd, Sydney

Hiscock, P. and Mitchell, S., 1993, Stone Artefact Quarries and reduction Site in Australia: Towards a Type Profile, Australian Heritage Commission.

PRIMEFACT 572, MINING BY ABORIGINES - AUSTRALIA'S FIRST MINERS www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/primefacts

Sullivan, C.J. and Opik A.A., 1951, Ochre Deposits, Rumbalara, Northern Territory, Commonwealth of Australia, Ministry of National Development, Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics, Canberra

Other Articles

1: Megafauna bones found at Lancefield bone bed in 1975.

.

2: Early Settlers Homes and Bush Huts in Australia.

3: Early Settlers in Victoria Australia.

4: Drought and Bush Fires in Victoria 1851 Black Thursday.

5: Chronology of Australian Major Bush fires.

6: Chronology of Australian Major Droughts.

7: Is there a risk of a volcanic eruption in Australia ?

Archaeological site at Mount William Lancefield Australia . ( 6 pages )

by Romsey Australia is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Australia License.

Revised February 2010